:1:

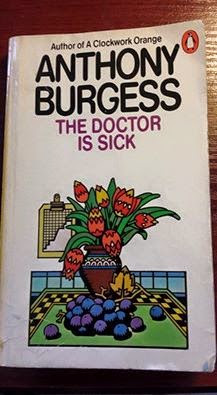

Burgess's fifth-published novel concerns a man hospitalised for a brain tumour in 1960s London: a smart, funny and (designedly) ghastly piece of writing. I read it in this edition:

It seems there was also an edition with cover-art inspired by Last of the Summer Wine:

Makes the first edition cover look a little tame, somehow:

Still: better than this one, with its too cartoonish intimations of Carry-On hi-jinks (the jinks in this novel are really rather low), and its use of the word 'pyjamaed' in plain sight on the cover, which is surely not actually a word at all:

The doctor of the title is Edwin Spindrift, a PhD in linguistics, home from a teaching posting in Burma because of a suspected brain tumour. He is accompanied by his faithless wife, Sheila. Theirs is an open marriage, although really only open on Sheila's side, since Edwin's inability to perform between the sheets is the root of the problem in the first place. Late in the novel Edwin wonders whether he should insist his wife apologise to him for her latest adultery, but then changes his mind: 'perhaps it was really up to him to ask her for forgiveness, for wives did not usually go around committing fornication and adultery if they were happy at home' [223]. Indeed. Sheila herself, slightly brittle and passive-aggressive during her infrequent visits to Edwin in hospital, is certainly unapologetic. She is staying at a local hotel, and rather than basing all her days around visiting hours at the hospital, she sends a succession of working class Londoners that she has met and befriended (and is in some cases sleeping with) from the local pub ('The Anchor').

1960s NHS hospitalisation and all that it entails is vividly and sometimes surprisingly drawn. I mean, I was born in an NHS hospital in the 1960s, and returned to one repeatedly throughout the decade and the one that followed it with the various health-related impediments Providence placed between me and growing-up, and which medical science helped me overcome, but I didn't realise that patients were allowed to smoke on the ward back then (really?). Edwin is X-rayed, electro-encephalogrammed and then has air injected into his cranium and is physically upended (another 'really?' moment; but checking with people who know, it seems this was a real treatment). The latter gives him a bad headache, and his tumour has already provoked synaesthesia and memory problems. His head is shaved, prior to surgery. But Edwin decides he's had enough of life on the ward, and does a runner. The bulk of the novel concerns his subsequent metropolitan peregrinations (this Burgess-idiom is catching, though, isn't it?), including stints in various bars and dives, meeting amongst others: two elderly Jewish twins called Leo and Harry Stone (what else would Joycefan Burgess call a Jew but Leo? and 'stone' is presumably a deliberate negation of the implied fertility of 'Bloom'); a sausage eating German matron whose English idioms inflected by her native tongue are; many cockney wide boys, amongst them Charlie (a window cleaner), Ippo (tea leaf and sandwich-board man) and Bob, who fences stolen watches ('kettles') and who takes a shine to Edwin, believing him to be 'kinky'. Bob's own kink is BDSM, and he kidnaps Edwin and locks him in his (Bob's) flat, begging him to beat him with his (Bob's) extensive collection of whips. Edwin escapes, has to flee gangster Bob's wrath, somehow ends up in a West End theatre, taking part in a televised 'Bald Adonis of Greater London' competition that has been organised to promote a film starring 'Feodor Mintoff', a version of Yul Brynner ('above the cinema entrance was a huge portrait of a bald actor with sensual lips and the sardonic eyes of a Mongol' [191]). The name of this film is Spindrift, also the name of a detergent Edwin sees advertised on the TV. Coincidence? Or evidence that Dr Spindrift is losing it? He is sure he sees Dr Railton, his consultant, playing trumpet in the orchestra accompanying the Bald Adonis show. When he wins the competition and is offered a chance to say something for the cameras, Edwin slips into full-on Burgess-curmudgeon mode. 'This must be a very big moment for you,' says the host:

'Not really,' said Edwin. 'I've known bigger moments. much bigger. As a matter of fact, I feel somewhat ashamed at having been a party to all this. So typical, isn't it, of what passes for entertainment nowadays? Vulgarity with a streak of cruelty and perhaps a faint tinge of the perversely erotic. Shop girls blown up into Helen of Troy. Silly little men trying to be funny. Stupid screaming kids. Adults who ought to know better. Here's my message to the great viewing public.' He leaned forward and spat full into the microphone a vulgar, cruel, erotic word. [198]The 1960s, Ladies and Gentlemen.

Some of this is uncomfortably close to The Right to an Answer, right down to reusing some of its jokes: the cat called 'Nigger' in that novel is now a dog called 'Nigger', the calling of whose name in public leads to an inverted-commas hilarious (actually wincing and poorly judged) set-piece late in the book, when certain London West Indians take exception to the word: 'they had had enough of white derision; they had learned that to ignore it was but to fan it. They were joined by two others of their race from another house' [188]. This leads to a fight with a gang of white youths. And in Right to an Answer too the Burgess p.o.v. character finds himself on national television and says outrageous things. But in other respects the two books are quite different. There's a similar linguistic density and fascination with dirt, mess, sprawl and the ordinary qualia of quotidian existence; but in Answer all the scattered elements accrete, are gathered together and arranged in a cause-effect pattern, because Burgess wants his story to move towards its Othello-inspired tragic denouement. The Doctor is Sick is a much more scattered product, with no big climax to work towards. A centripetally circular construction.

We are increasingly unsure, as we read on, how much of this is suppose actually to be happening to the hapless Edwin, and how much is a fever-dream hallucination. In the penultimate chapter he wakes, back in the hospital, his wife at his bedside: she tells him the operation has been a success, denies that the things Edwin said happened did happen, and informs him that he has been sacked from his Burma job due to his ill health, and that she is leaving him. 'The trouble is,' Edwin ruefully notes, 'that I'm the last person in the world to say that this happened and that happened. I don't know' [228]

Edwin loves words more than he loves his wife; and his modus operandi through his peripatetic story is to unload mini-lectures about words, etymologies, orthography and semantics on all and sundry. Dr Railton, testing his brain function, asks him the difference between 'gay and 'melancholy'. '"There are various kinds of difference," said Edwin. "One is monosyllabic, the other tetrasyllabic. One is of French the other of Greek derivation. Both can be used as qualifiers, but one can also be used as a noun."' [21]. The doctor notes 'you've got this obsession, haven't you? With words?' But Edwin doesn't agree. 'It's not an obsession, it's a preoccupation. It's my job.' One consequence of this protagonistic preoccupation is that the novel is littered with QI factoids, which makes for a quite interesting read: that the 'y' in 'ye olde tea shoppe' is not a 'y' at all but an approximation for the Old English letter thorn; that 'Sam Weller did not interchange "v" and "w": he used a single phoneme for both—the bilabial fricative. But a recorder like Dickens, untrained phonetically, would think he heard "v" when he expected "w", "w" when he expected "v"' [45]. If it gets tiresome, or at least if it gets in the way of the novel's ability to recreate emotional depth, then that's deliberate too:

Love, for instance. Interesting, that collocation of sounds: the clear allophone of the voiced divided phoneme gliding to that newest of all English vowels which Shakespeare, for instance, did not know, ending with the soft bite of the voiced labiodental. And its origin? Edwin saw the word tumble back to Anglo-Saxon and beyond, and its cognate Teutonic forms tumbling back too, so that all forms ultimately melted in the prehistoric primitive Germanic mother. Fascinating. But there was something about the word that should be even more fascinating, to the man if not to the philologist: its real significance when used in such a locution as 'Edwin loves Sheila'. And Edwin realised that he didn't find it fascinating. [140]

:2:

It's a rather obvious thing to say, but this novel takes its key inspiration from the two late episodes in Ulysses: dividing itself between, first (like 'Oxen of the Sun'), scenes set in a hospital inflected through an acute sense of linguistic history, and then (like 'Circe') a phantasmagoric meander around a city, mostly at night, in which an unhappy, erudite young (ish) man encounters all manner of grotesques, oddballs and weirdos. But formally it is more Finnegans-Wakey-wakey than it is Ulyssean. This is mostly to do with a deliberate structural circularity, a plot defined by recurrence and a general commodius vicus-ishness, whereby Edwin keeps coincidentally bumping into the same people, having the same experiences. Late in the novel he meets an old University friend called Aristotle Thanatos, a Brit of Greek extraction, known as 'Jack'. Or does he? Did he ever have such a friend? Could, for example, anybody exist with such an improbable name? Back in hospital he puzzles over this, not least because the very wealthy Thanatos has offered him a job. Thanatos means death, of course. Aristotle is cockney rhyming slang for bottle; which in turn ('bottle and glass') means that it means arse. Hence: 'Jack'. ('I don't know where you people ever got the Jack from', Thanatos complains; and Edwin explains 'it was to protect you from the vulgar and uninstructed. Aristotle, to the British, has always had a ring of the unclean' [209]. Ring. Ho ho. But see also: jacksie). And actually its the circularity of this piece of rhyming slang that really fascinates Edwin: you say 'bottle', to avoid having to say something so vulgar as 'arse'; and you say 'Aristotle' for bottle, which you then shorten to 'aris', which sounds pretty much like you're saying the word you were trying to avoid in the first place. During one of his impromptu lectures, in an unlicensed drinkery earlier in the novel, Edwin expatiates on precisely this:

"The peculiar forms of Cockney are ... conscious perversions of standard forms. Take rhyming slang ... Arse," said Edwin, loudly, "becomes bottle and glass. There is then a kind of apocope, intended to mystify. But bottle itself is subjected to the same treatment, becoming Aristotle. Apocope is again used and we end with Aris. This is so like the word originally treated that the whole process seems rather unnecessary." [110]It's as if, in seeking to avoid a taboo, we undertake a complex series of knight's-moves that bring us inevitably back to the taboo. Which is what? Death. The bibulous Aristotle Thanatos, who may or may not exist: bottle death, in a novel written by a heavy drinker who believed himself to be dying. Bottle death, ending a novel that is—its linguistic grace notes and digressions aside—fundamentally the story of an unhappy marriage breaking apart that patently draws (as did The Enemy in the Blanket) on Burgess's own circumstances with Lynne. Lynne who literalised 'bottle death' by drinking herself into the grave within eight years.

But why stop the apocope there? Perhaps the novel is more anally mortifying than drink-sozzled. There's a great deal of drink and drunkenness in it, certainly; but there are also several key scenes inside toilets (in one, Edwin forces himself into the same toilet cubicle as a man, in order to hide from pursuing, furious Bob, only to discover that the man is his boss), and the usual Burgess/Enderby fascination with shitting, the stuff we might call Joycean if we wanted to dignify it. There's a good deal of stuff to do with holes. Edwin delivers a lecturette on the etymology of the word 'cunt' [100]. In one drinking place, he listens to a song sung by 'a lank young man with glasses, a turtle-neck sweater and hair geometrically straight', accompanying himself on the 'Spanish guitar':

For them that looked for the way out and found it:This goes on for pages: 'The holy, the whole, when seen through the hole/Not seen wholly but only whole holy deliverer from/This' [160]. Man, woman, bottle. Aristotle, arse. On the wall of this drinkery are examples of 1960s art by F. Willoughby. 'Some were bigger than others, and the plain painted backgrounds varied in violent poster-colour, but every one of F. Willoughby's pictures was a portrait of a circle. "They're only circles," whispered Edwin. "Circles, that's all they are."' [159]

This.

There are holes that grew as doors with looking for them,

And for those that walked through with their heads high as kites.

This.

Where were the holes?

In man, in woman, in bottles, in the tattered book picked up from the mud on the rainy day by the railway junction.

But the whole of wholes, the hole of holies, where was where is

This? [159]

Waste may be the key, actually. Insofar as the novel hints at a theme, it is that Edwin has wasted his life. In You’ve Had Your Time Burgess sums-up: ‘in The Doctor is Sick the philologist Edwin Spindrift purveys nothing valuable, while the Jewish twins who run an illegal club at least try to get people drunk' [YHYT, 13]. And the London through which Edwin wanders is a horrible enough place, run-down and seamy and dead. The novel's density of references to and quotations from The Waste Land make this point, too. At the end, Edwin struggles to recall some Greek to say to Aristotle Thanatos: 'but nothing would come. "Apothanein thelo," he said instead, without intending to say it' [214]. That's the end of the epigraph to Eliot's poem, of course: 'I want to die'. A few pages later Edwin doubts the existence of his friend: 'He racked and sifted his memory for Aristotle Thanatos. It was the sort of name a man might make up, like Mr Eugenides the Smyrna merchant' [224] Oho! You remember that Eliot's poem quotes the opening lines of the sailor's song from Tristan und Isolde?

Frisch weht der WindSo does Burgess, in a pub, where a cockney named Les:

Der Heimat zu,

Mein Irisch Kind,

Wo weilest du?

began to sing disconcertingly the sailor's song from Tristan und Isolde. He sang it in a strange and apochryphal translation:This is pretty funny, I guess: confusing Kind and Kuh. Early on, Edwin assumes his nurse is Russian and addresses her ('spasebo tovarishch'); she replies 'you need not thank me. It is my duty. Besides, I am not Russian' [17] and I suppose we can assume ('Bin gar keine Russin, stamm’ aus Litauen, echt deutsch') that she is Lithuanian.

"The wind's fresh airs

Blow landward now.

Get up them stairs,

You Irish cow." [99]

But look: piling up all these sorts of word-game instances (and there are lots) is a tedious business. There's certainly a bleakness in the comedy, here; everything is wasted, tending towards death. The doctors are looking for something in Edwin's head, something in his white matter, something deadly. They search and search. Edwin goes questing to, looking for ... what? Something. Restlessly moving on, trying to find it. He is the doctor and he is Moby Dick. Sickness is a wasting away, and this is the wasting away land. He is Ahabic, and the sea across which he travels a desolate one. Öd’ und leer das Meer.

:3:

The doctor is a bit moby, sure. But then again he's not a proper, medical doctor. In a hospital setting he's effectively a fake doctor. A quack. The thing about Moby Dick is that it embroiders, howsoever digressively, a basically linear narrative. Or perhaps it would be better to say, the story is dragged along in the straight-line wake of its prime signifier, the white whale. Ulysses can't help but fall into Odyssean patterns of a quest, journey, a destination, a straight line, a goal. The Waste Land is a parched and urbanised quest narrative. But The Doctor is Sick is repetitive, circular, all digression and no through-line. Edwin is in hospital. In chapter 3 he sneaks out of the hospital and has his first drink at the maritimely The Anchor. Chapter 4 he's back on the ward. Chapter 11, he decides to leave again ('Death was in the hospital: you could hear it snoring in the ward. Life was outside. He must leave at once.' [72]—what was it Larkin asked? Why aren't they screaming?). Chapter 12 he's out in the world again. In chapter 29 he's surprised to find himself back in the hospital. In chapter 32 he sneaks out of his bed in the night, steals some clothes and escapes the hospital again. There's a kind of randomness to all this in, out, in, out; a sense not of narrative pattern but of the awkwardly piled-up way events succeed events in the real world. And, actually, that's one of the key things the novel is doing. Edwin's tumour deracinates his ability to process the world around him into a meaningful gestalt; so he encounters its multifariousness as clutter. The prose is full of things like this

There was a coffee-bar, a steak-house, a chicken grill, a potato parlour (Steaming Jumbo Murphies Slashed And Buttered), a yumyum pastry ship, and even a jungly-looking place called Lettuce Land. Edwin eventually found a Pickwick Breakfast Bar, sat on a stool of contrived discomfort at the counter and looked at the menu. He proposed flapjacks with maple syrup, haddock wth two poached eggs, pork sausages and bacon with rognons sautés, toasted muffins, marmalade, much coffee. [172-73]Or this account of Leo's conversation:

Leo spoke of amation, of the importance of afters and the special role of the man in the boat; of how to tell heads or tails by the sheer sound; of the private lives of Shakespearian actors; of perversions in Hamburg; of a Thai lady contortionist he had lived with; of a rich queer he had nearly lived with; of great gang figures like Big Harry, Tony the Snob, Quick Herman, Pirelli; of Qwert Yuiop, the Typewriter King. [112]Visiting him in hospital, Charlie brings him as a gift not one wank mag, as you might expect, but a whole clutch of them: 'he pulled from his side-pockets bunches of gaudy magazines—Girls, Form Divine, Laugh It Off, Vibrant Health, Nude, Naked Truth, Grin, Brute Beauty' [13]. This piling-up of descriptive detail is an old strategy of the Realist novel, of course; and Burgess's seeming higgeldby-piggeldness serves its own purpose. It creates the effect not of Rabelaisian plenty, but an odd sort of transience, a sense of over-production, linked perhaps to the ephemerality of mass production. Everything flashes past Edwin's eyes. Midway through the story, on the run from Bob, he passes through a house:

Edwin raised himself by his hands, kneed the wall-top, found an overgrown garden on the other side, then swung himself over. He rested a second or two against the wall. Ahead was a house of four storeys and a basement, one of a row. Dusk had almost become dark. He stumbled through rank grass and bindweed, nearly fell over an unaccountable coil of barbed wire, clinked several bottles together like a glockenspiel solo, then came to an open back door, a scullery with a very bright light bulb. A pale young man th very oily black hair was leaning over the sink, wearing a woman's apron with frills. He was peeling onions under water but blinded with crying. Edwin stole across the scullery, through a dark kitchen into a hallway a voice called: "Is that you, Mr Dollimore?" Edwin passed a card showing times of church services, another with the legend SINNERS OF THE STREETS (X), a map of London, a wall telephone, opened the front door on which a card—HOUSE FULL—was hanging from a tin-tack. The street was far from empty. [120-21]The novel has nothing more to say about Mr Dollimore, the onion-peeling-man (who, since the onions are under water, is presumably weeping through grief, rather than irritant airborne sulfenic acids. I wonder what has upset him so?) or this house. It is introduced without preliminaries, and then the story passes on. It's suggestive, but even that suggestiveness gets lost in the blizzard of all the other stuff that the novel hurries on to. There's something of this in Moby Dick, I know; and a lot more in Zola or Dickens.

Dickens makes an interest comparison with Burgess, actually. Two capacious, busy, comic novelists attempt to reproduce the textures of the world in which they find themselves. Literary criticism, in almost all cases, tries to clarify things. Accordingly one of the problems the literary critic faces is: what to do with texts that resist the cleanness and order implied by clarity; or to put it more precisely, texts in which the process clarification smooths away or fails to transfer crucial aspects of the original. In terms of Dickens, I’d say there are two qualities: one—about which critics often speak, sometimes with a mournful acknowledgement that it slips through the net despite being patently one of the most important aspects of Dickens’s art—is his humour, his comic brilliance, his ability to make us laugh. The problem, of course, is the old one: a joke explained ceases to be funny. But there’s another element integral to Dickens’s work as a novelist that clarification misses, and that is, precisely, his clutter. Dickens’s novels are full of stuff: lots of objects, myriad cultural references, in-jokes and out-jokes, subplots, interpolated tales, diversions, descriptions, catch-phrases and quirks and oddities. His novels teem, and that is precisely part of their distinctive appeal. But short of a bald taxonomy of the multitudinous items that constitute the clutter (and that is in itself a violation of the logic of clutter, an ordering of it), what can the critic hope to do with it? Clutter clarified isn’t clutter anymore. And so, like a big white fish, Burgess's novel slips through my critic's fingers and swims free.